Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Several years ago, I was standing in our school lunchroom watching hundreds of students eat breakfast.

I was positioned in the middle section of the room, and the front doors of the school were about one hundred feet across the room from me. Dozens of students were entering when I saw one high school boy who caught my attention. He was so far away, I could not see his facial features, but his demeanor and walk gave me a quick pause.

I decided to follow my hunch. I walked across the room, and as I approached him more closely, he tried to avoid eye-contact. But I casually stepped closer and asked him if I could talk to him in private for a minute. Once he was in my office, I invited another administrative team member to join me, and my hunch proved accurate.

The boy was under the influence of marijuana and was also in possession. Later that morning as we worked through meeting with parents and school discipline procedures, he suddenly looked up at me and asked, “How did you know I was messed up from all the way across the room?” I didn’t know how to explain how I knew. I had been a school administrator for more than ten years, and a lot of my observations came second nature.

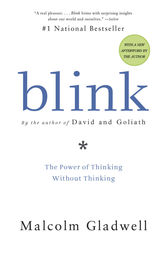

This summer I enjoyed reading Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. In the book, he explains the importance of understanding your adaptive unconscious — the small ways we discern situations and make decisions that often happen in a split second.

Throughout the book, Gladwell uncovers three main takeaways:

- Decisions made quickly can be as important as ones made over a long period.

- Sometimes our instincts betray us.

- Our first impressions and snap judgements can be educated and controlled.

Slicing Information

Gladwell explains that experts often “thin slice” information for quick judgements. For instance, he talks about the ability of experts in ancient artifacts to be able to tell the difference between a fake and an authentic piece of art by just glancing at the work. He describes the work of social scientists who can predict whether new couples will stay together long-term just based on a few minutes of watching them talk and interact. The lesson? Over time, you develop abilities to “think slice” large amounts of data or information that help with decision-making.

Instincts That Betray Us

But he also explains ways that our unconscious ideas can infiltrate or manipulate reality. One startling example is the way we perceive gender and race. Gladwell cites numerous studies where the majority of people (even people of diversity) will misjudge or assign more negative emotional levels to people of color, men who are shorter in stature, or to women in general.

Gladwell is the child of an integrated family. He shares how he participated in a scientifically designed computer programs that required participants to assign emotions to photos. To his surprise and embarrassment, he inevitably assigned more negative emotions to minorities. These blind-spots in our unconscious can be dangerous if they cause us to make biased decisions we are unaware we are making. In schools, this often happens in the ways we unconsciously pay more attention to the behavior of boys.

Educating Our Impressions

Finally, Gladwell explains how we have the capacity to train ourselves in the ways we make snap judgements. One example he gives is in police work. He cites research that police who pursue suspects in high speed chases almost always overreact with excessive force. Police academies are now adapting this research to instruct officers against high chase pursuits and against confronting suspects while alone. Officers are also learning to repeatedly mock-play crisis scenarios so that they do not freeze or overreact in real life ones.

For school leaders, you may not always think about the power of safety drills, crisis scenarios, or mock-playing uncomfortable scenarios. But what your mother told you is true: practice makes perfect. When it comes to training your unconscious to not overreact, training and education is essential to making better snap decisions.

Implications for School Leaders

What are some takeaways for your leadership when you consider Gladwell’s lessons?

1. Don’t underestimate your ability to “thin slice” complex situations when you’ve had deep experience in managing similar scenarios in the past.

Your experiences significantly inform your ability to make important judgement calls. Decisiveness can be the result of deep knowledge and experience. For instance, as an instructional leader, you will spend a lot of time observing and evaluating teachers. Rubrics and written instruments are an important way to maintain consistency, but these tools don’t replace your good judgement. Even in content areas where you may not be experiences, overtime, you can pretty quickly assess whether or not learning in happening in a classroom.

Yes, you are still required to do due diligence with documentation, but it doesn’t take long to identify good teaching from bad teaching. Students figure this out quickly too. Why? They’ve had a lot of experience being taught by strong or poor instruction. Don’t ignore those basic instincts that come with your own experience either.

2. Don’t overestimate your ability to follow your instincts.

Just because you may be good at “thin slicing” in some scenarios, you do have an excuse from consistently reflecting on areas where you may have a hidden bias. Ask others where they may perceive your blindspots. Study your own data on how students are performing in academics and behavior. Do you see tendencies toward some sub-groups struggling more than others? Ask yourself how you are providing equal access to resources, opportunities, and recognition to all students.

I remember once when a 16-year old female student was in trouble for an emotional outburst she had with another girl. After meeting with the girl, I gave her a stern lecture on her behavior and called her parents to explain the school consequences for her misbehavior. While talking to the parents, I realized this girl was on an IEP. When I dug into her file, I saw where her processing abilities were more similar to a 3rd grader than a high school sophomore.

The “light bulb” moment helped me realize why she was having such a hard time responding to my conversation the ways her peers were responding. Needless to say, it changed the way I spoke, responded, and guided her in future situations.

Don’t overestimate your abilities in snap-judgments. Consistently look for what may be hidden in a situation. If or when you see areas where you may need to readjust your perspective, do it.

4. Educate yourself so that you have stronger control in good decision-making.

Gladwell shares research that shows our tendencies to place too much importance on appearance versus substance. In addition, he shares ways professionals practice scenarios in advance so that they are better prepared not to make wrong decisions.

One example for school leaders is managing difficult conversations. I’ve often seen instructional coaches role-play difficult conversation scenarios with teachers or other administrators in advance. Doing this lowers anxiety and teaches better conflict-resolution skills.

Open your eyes to the perspectives of others. This past year, I had an administrator friend point out to me that a very small percentage of minority males serve in school leadership positions. As I looked at my summer reading list, I decided to expand my own reading to better educate myself on perspectives on minority leaders.

Here are a few books I have also enjoyed reading during the past months to help me keep expanding my own thinking on ideas from important leaders with historic and contemporary perspectives:

Watching Our Crops Come In by Clifton L. Taulbert

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois

Think about ways you can better inform your own ideas and mindsets so that you don’t become subject to a fixed-mindset in your judgements and perceptions.

Let’s Wrap This Up

I have probably called it wrong as many times as I’ve called it right in good decision making. That may be a sad commentary on my personal and professional judgement. But the reality is that you always have room to grow.

Gladwell’s book is a fascinating study in how you tend to call it right more often when you have deep experience with a situation or subject. But it is also a good reminder that you may be working with blindspots when it comes to your perceptions and judgements of others. Most importantly, he shares how you can actually grow your abilities through practice and education so that you make better choices when called on to make quick decisions.

Now It’s Your Turn

Can you think of a time where a quick judgement has served you well? Can you remember a time where you may have needed longer study of a situation to make a better decision? Don’t be frustrated that both realities exist at the same time. Gladwell’s research shows that we are good and bad at decision-making. Understanding this is one step toward improvement. Is there a book or resource you may need to read to have a better perspective on your students or the people with whom you work?

Sign-Up For Free Updates and Ebook

You can automatically receive new posts and a free Ebook, 8 Hats: Essential Roles for School Leaders. Let’s keep learning together!